My attention was drawn to an article in The Age (also published in other Fairfax newspapers) on 23 April, entitled “Time to let go: selling in May could be a winning strategy” written by ATAA member Alan Clement. The “Sell in May and Go Away” subject comes up around this time of every year with market commentators putting different spins on the old adage, some for and some against, so I thought that I would try and put it to rest once and for all.

Alan’s article looked at historical data on the S&P500 going back to 1998. 13 of the 15 years span a secular bear market. I decided to run some research that went back to 1950 and then back to 1928 which includes multiple secular bull and bear markets to determine whether the “Sell in May and Go Away” strategy had an edge or not and, if so, how good an edge.

The basic rules of the strategy that I researched were to buy in the last week of October or the first week of November, depending on which was the closest Monday to the end of October, and to Sell on the last Friday of April. I chose the last week of October, as opposed to earlier in October, to avoid or minimise the effect of the big falls of 2008, 1987 and 1929 – yes hindsight bias. When buying at the end of October each year, the same amount of capital that was divested in April was re-invested in October later that year.

The theory is that one will avoid the so-called notorious market periods from May to October in the North American and European summers when people supposedly go away on holiday and hence reduce your exposure or exit the market, and that one will engage the market during the so-called Christmas and New Year rallies from November to April when people are supposed to feel positive.

Many market commentators investigate this “Sell in May and Go Away” phenomenon by measuring the market performance in individual months and then average them, or use some other statistics, to determine whether this phenomenon is actually true of not.

My view is that this is best done by using an equity curve that emulates having managed a portfolio that bought and sold the index over a large sample of years to capture as many different market conditions as possible. Then compare this portfolio equity curve to that of ‘buying and holding’ the index and to doing the opposite, i.e. buying in May and selling in October of each year.

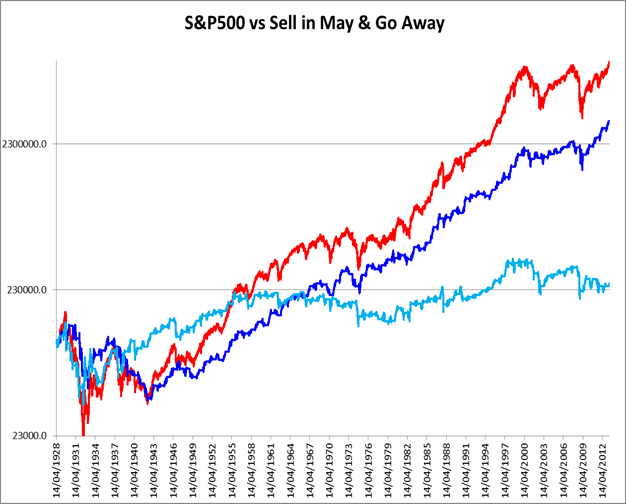

The red line in the chart below is a log chart of the S&P500 from April 1928 to May 2013. The navy blue line is the equity curve of “Sell in May and Go Away” until the end of October each year. The light blue line is the equity curve of “Buy in May and Make Hay” until the end of October each year.

It is obvious from the above equity curves that over the entire period since 1928

“Sell in May and Go Away” performed better than “Buy in May and Make Hay”, however still did not match or outperform buying and holding the index.

The log graph belies the final difference between the index and the “Sell in May and Go Away” portfolio value. The index grew from $100,000 to $8,472,916 at 5.36% compounded per annum (CAGR) whilst “Sell in May and Go Away” grew to less than half at $3,281,952 which is 4.19% CAGR. “Buy in May” did not make hay growing only to $257,959 at 1.19% CAGR.

Maximum drawdown’s were not that different: -86.45% on 1/06/1932 for the S&P500 index, -69.74% on 28/04/1942 for the “Sell in May and Go Away” strategy and -72.65% on 1/06/1932 for the “Buy in May and (don’t) Make Hay” strategy.

However, note that “Buy in May and Make Hay” matched and then outperformed both the other equity curves until the early 1950’s. If market commentators where conducting this same debate back in 1952 they would probably have concluded that “Buy in May and Make Hay” was a better strategy than “Sell in May and Go Away”!

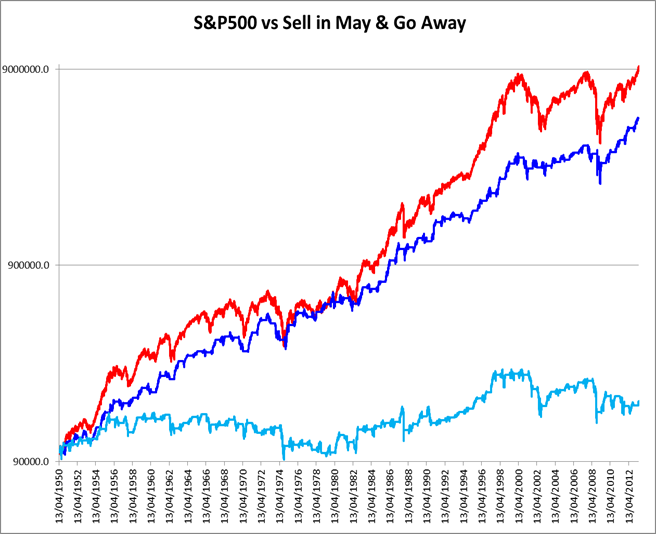

The next chart analyses the period from April 1950 to current.

Again “Sell in May and Go Away” outperforms the buy in May timing and again does not outperform buying and holding the index.

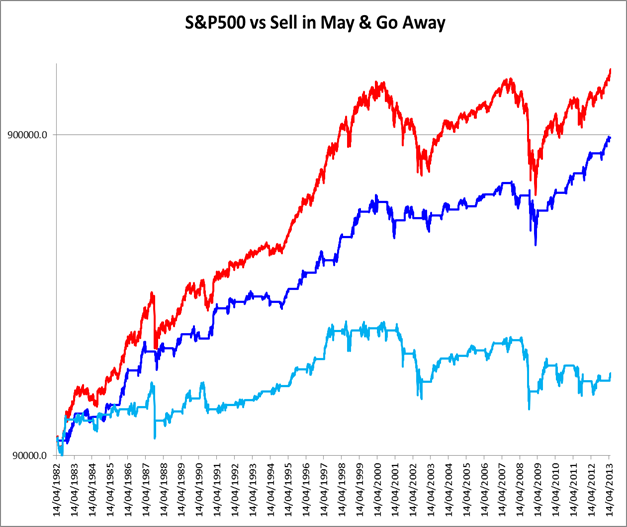

The next chart zooms in to the period from April 1982 to current, a period of 31 years, with a similar outcome.

The statistics are even more convincing for this last period. The respective CAGR’s for the S&P500, “Sell in May and Go Away” and buy in May and not make hay were 8.96%, 7.25% and 1.57%. The shapes of the line graphs above show that the difference between the two timing strategies has become even more stark since 1997 and during the secular bear market since 2000.

From the above analysis it might be concluded that:

- Both timings have an edge in that both are profitable. The survivor bias of an index alone should ensure this.

- “Sell in May and Go Away” has a better edge than buying in May and selling late in October. This shows that the market does perform far better during the November – April timeframe than the May to October timeframe.

- Neither timing strategy has an edge over merely buying and holding the index. However, buying and holding the index could not be done prior to 1992 (since the inception of ETFs).

- The “Sell in May and Go Away” phenomenon only really started in the early to mid 1950’s. Why is another subject altogether.

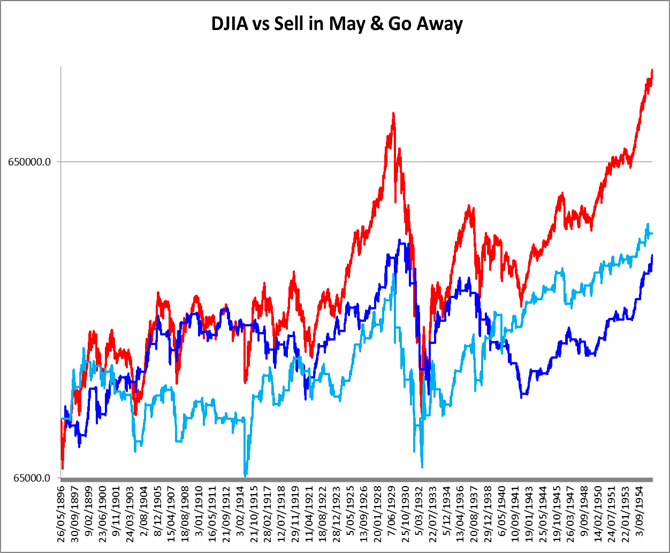

I decided to do a little more research to determine whether this post 1950 notion might carry any weight. Using data on the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) from May 1896 to April 1956 and using the same rules as used on the S&P500, the chart below resulted.

Over this 60 year period there is no evidence that the “Sell in May and Go Away” phenomenon was in effect in the market. In fact, “Buy in May and Make Hay” was the better strategy. Note how much better it performed than “Sell in May and Go Away” from 1932 to 1956 following a deeper drawdown during the 1929 crash.

One of the problems with trying to form a view from such analysis is that the sample of 85 years (=trades) may be too small to be sufficiently statistically significant and on which to base an investment strategy going forward from here.

Even though the phenomenon seems to have accelerated over the 12 or so years, which has been a secular bear market, there is no reason why the market psyche with respect to this phenomenon couldn’t return to that of the 60 period prior to 1956. Indeed, the other period that “Buy in May and Make Hay” did very poorly was during the 1965 to 1982 secular bear market (see the first chart above).

My parting points are these:

- Anything can happen. It is far better to keep an open and neutral mind to the market at all times rather than have a LOLO (Lock On Lock Out) mindset. Rather expect and assume that anything can happen at any time.

- People look for patterns. It’s inherent in all of us to look for reasons to explain why. Finding patterns that may reoccur is not a bad thing but putting too much energy, focus and weighting on any one pattern to the exclusion of all other information can be dangerous to one’s investment accounts.

- People are convinced in small samples and by recent events. If we had two or three years in a row when the markets climbed strongly in May to October and fell sharply in October to April how would we collectively react? Is this possible? Of course, “anything can happen” so we should keep our minds open to the possibility rather than closing them based on a bias.

- Trying to match the index is simply not good enough. As active investors we need to aim at outperforming the index by at least four compounded percentage points per annum.

Investors should use these points in devising their approaches to decision making in the market.

6 Responses

If the withdrawn funds were placed in a 4% term deposit for the six months of being out of the market, CAGR of the two timing options would be 2% higher so the sell in May would beat the ‘index and hold’ by a little.

Hi Gary,

Once again you surprise us all this bega the question though what would happen with a Spa portfolio which bought in may and ran away

I think it would underperform but I stopped guessing some time back!!!!

Response to Comment by Peter:

The 4% interest p.a. for 6 months of every year compounded over 85 years would make a huge difference.

However, the objective of the exercise was to determine whether the net raw move over each of the 6 month periods added or detracted from the overall raw movement of the market.

To achieve this I omitted interest in the active buying and selling of the index equity curve and also omitted the effect of dividends being included in the index, that is, the S&P500 Total Return index.

FYI, the effect of dividends over a full year on the S&P500 have been higher on average since 1988 than an average of 4% p.a. interest for half a year, viz 2.27% vs 2.12%. And dividends were higher in the United States pre 1990’s.

I did run these simulations but after analysing the results concluded that they did not add value to the exercise and rather confused it.

For instance, what interest rate to use when they have been > 10% and < 2%p.a. and dividends have been > 5% and < 2% p.a?

Regards

Gary

Thanks for sharing all of your hard work Gary. A very interesting result. The sell in May graphs look a lot less volatile so would maybe be better if you we’re using leveraged products like CFD’s.

Well what fascinating reserach: yet does not make me money. As Gary says, “anything can (and does) happen”. That’s why one Drives with Brakes, and Trades with Stops. Again, the past week’s market moves were a fine test for me. Together with SWS signals and my additional tight stops in some circumstances of overall risk management, and ruthlessly applying my rules, I fled like a rabbit in full flight, swinging from 95% invested to fully cashed up.

Indeed I felt terribly sorry to be slaughtering some of my favourite lambs that did so sweetly for me.

Yet it had to be done.

Overall that was all very exciting.

And the result is an enormous excess performance above the ASX index for the year.

Now I’m bored and looking for new opportunities, finding none that suit my (mainly SWS) rules. And the human inclination is to go and find new action, and make it happen as one can in most businesses. Yet for me right now boring is best, watch and wait, if nothing happens, nothing happens. Of course “anything can happen, at any time” (and even without warning,see last week!). Yet one can’t make it happen. Important to resist one’s “human nature” in the markets!

Indeed I needed to add: Thanks Gary & Co at SWS for such fine software and education!

Plus please fix my typos in the above comments just sent…….